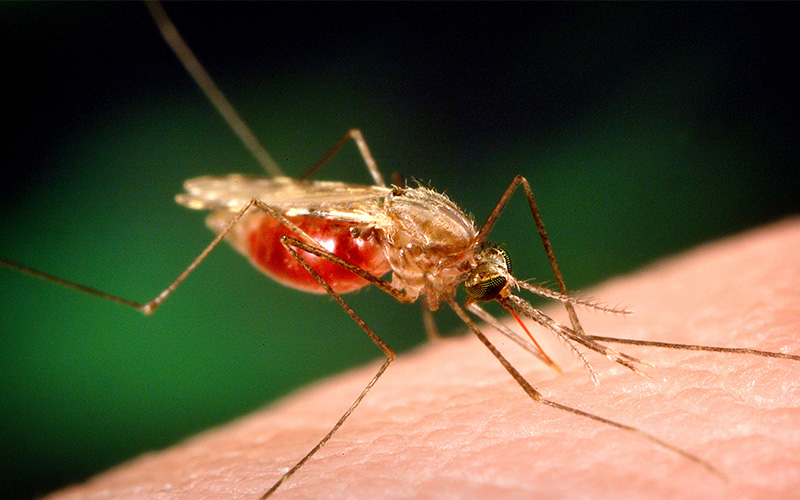

Today, as we mark World Malaria Day, we’re highlighting innovative approaches that can drive progress towards eliminating this deadly mosquito-borne disease.

At Burnet, our researchers are rethinking how we track mosquito exposure — a key factor in malaria transmission.

The World Health Organization identifies the surveillance of mosquitoes that transmit malaria as a key strategy for elimination. But current tracking methods rely on insensitive techniques, such as human baited traps that are labour-intensive, expensive and prone to biases.

Our recent study found human antibodies developed against proteins in the saliva of malaria transmitting mosquitoes can serve as markers to estimate how often people are bitten.

This is particularly relevant in regions where environmental factors — such as climate, land use, housing conditions, and human behaviour — increase exposure to mosquito bites and create malaria hotspots.

This study suggests using antibody-based surveillance can provide a logistical and practical way to overcome the constraints of traditional methods of monitoring mosquito exposure and malaria risk.

Lead author of this work, Dr Ellen Kearney explained how she used satellite data on environmental and climate factors like temperature and rainfall, along with human antibodies specific for mosquito saliva and malaria parasites, to create detailed risk maps of mosquito biting and malaria transmission.

“These maps offer a more detailed view of how often people are exposed to bites, in ways that previous models could not,” she said.

Professor Freya Fowkes, head of Malaria and Infectious Disease Epidemiology at Burnet, said this approach can be scaled up into existing malaria surveillance networks throughout the Greater Mekong Region, which includes Cambodia, China (Yunnan Province), Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam — where drug-resistant malaria remains a major public health challenge and cases are unevenly distributed.

“By identifying high-risk areas, we can make sure vector-control efforts are used where they’re needed most, making the best use of limited resources and continue working towards malaria elimination,” she said.